TLDR

- The annual budgeting process is broken but can be fixed using centuries old techniques.

- Using demand for products/services to create budgets, not last year’s budget as a baseline.

- The critical component is to properly calculate fully-burdened Unit Costs.

- The budgeting process can be changed in stages, starting with Academic Program financial forecasts.

- It’s important to fix now, because budgets drive change more than strategic plans, and Higher Ed needs to change to address all of the current challenges it faces.

There is growing consensus in the accounting world, that the annual budgeting process is broken. According to Gary Cokins, an internationally recognized expert, speaker and author in enterprise and corporate performance management, the annual budget is “…often scorned as being obsolete soon after it is produced and biased to politically muscled managers who know how to sand-bag their budget requests. Consolidating managers’ budget spreadsheets is insensitive to demand volume in the next fiscal year.”

Gary’s recommended approach to fixing the process is “initially using activity-based costing (ABC) as the source to calculate calibrated unit-level consumption rates for “capacity-sensitive driver-based budgeting”. Those consumption rates are needed for zero-based budgeting (ZBB), rolling financial forecasts, and any what-if scenario planning.”

Simply stated, using demand for products/services to create budgets, rather than last year’s budget as the baseline.

Simply stated, using demand for products/services to create budgets, rather than last year’s budget as the baseline.

Industrial engineers have been using this approach since the industrial revolution, using product volume and mix multiplied by unit-level consumption rates to determine the required resources.

Gary discusses his approach in the video below:

Higher Education Budgets

From a Higher Education perspective, Chris Grange the former COO of the Australian National University states that budgeting drives behaviour more than the strategic plan.

William F. Massy, professor emeritus of education and business administration and former vice president and vice provost at Stanford University, states in his latest book Resource Management for Colleges and Universities that “Budget-making and related resource allocation processes set the boundaries for the university’s internal economy. They provide levers for institutional steering and the stimulation of change. Steering requires choices about whether to invest in new programs or activities or to disinvest in current ones…”

book Resource Management for Colleges and Universities that “Budget-making and related resource allocation processes set the boundaries for the university’s internal economy. They provide levers for institutional steering and the stimulation of change. Steering requires choices about whether to invest in new programs or activities or to disinvest in current ones…”

The objective with these new types of budgets is to “stimulate improvement at all levels of academic granularity. Sometimes this stimulation comes through explicit channels, as when the budget system provides incentives or rewards for particular kinds of activities, most often, though, it arises from deep-seated academic desires to further student learning, research and other worthy institutional objectives – desires that can be empowered by new data and more informed conversations. Higher education should treasure these desires, and care should be taken that no model or administrative process undermines them.”

So in summary, the traditional annual budgeting process is broken, however it’s fundamentally important for driving change in an institution, particularly at the moment where rapid change is inevitable with pressures on higher education institutions from a number of different sides – inflation, rising interest rates, reduction in student numbers etc. So the annual budgeting process needs to be fixed, but to completely reengineer this entire process is a major undertaking.

A Way Forward

If you want to change your Higher Ed institution to address current challenges and the budget is a key tool to drive this change, it makes little sense to set a starting baseline as last years budget. The better starting point is to set a budget based on expected change in the demand for programs (existing and new), as well as change required to support the strategic direction of the institution and calculate the resourcing required to support this change. Gary used the term driver-based budgeting, I prefer Resource Consumption Budgeting (RCB), which aligns with Bill Massy’s Academic Resource Management (ARM) framework.

Rather than take a “big bang” approach to reengineer the budgeting process, it could be approached in stages, starting with academic program budgeting, that is, using unit costs and expected demand to forecast academic programs financial performance. After all, academic programs are core to the higher education business, so it’s an obvious starting point.

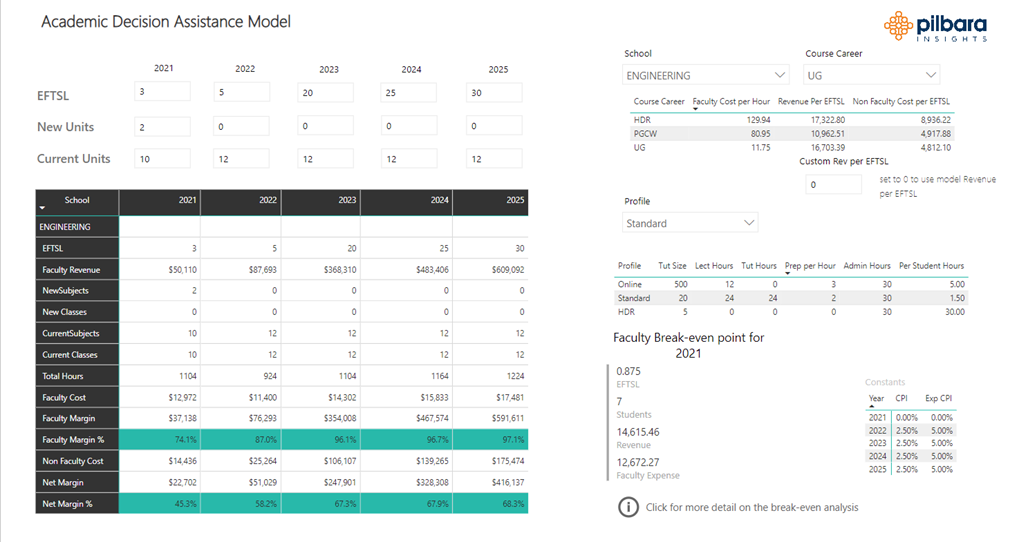

The Academic Decision Assistance Model (ADAM) tool is a perfect first step in this process revamp.

The ADAM tool uses unit cost data from the underlying ABC model, these costs were derived from 10’s millions or over 100 million calculation paths based on cause-and-effect drivers, so provide a robust mechanism for forecasting costs.

Costs are categorized as either faculty or non-faculty. Non-faculty cost is divided by EFTSL (Equivalent Fulltime Student Load – similar to Student FTE) and faculty cost is divided by academic delivery hours (time taken to deliver teaching, mark exams, admin, liaise with students etc.) – this provides the tool with the unit costs that can then be used with a program EFTSL forecast and a program profile to calculate a financial forecast. The tool will also calculate a breakeven point, that is, the minimum number of students required for the program to generate enough revenue to cover the faculty cost of delivery.

The tool, in it’s current form, has been developed for forecasting the financial performance of NEW programs, this could be extended to include existing programs and also the entire program portfolio for the school and/or university for the next 12 months, to support the development of the new budget.

A future iteration of the tool will include benchmarks, so not only could you compare the forecasted budget to last year’s budget, but also to the costs from peer institutions, although this can only be done at the Field of Education (FoE) level and not the individual program level. Annual benchmarks are already provided to client institutions, so it’s a relatively simple process to include in the ADAM tool.

Conclusion

The annual Higher Ed budgeting process is broken but there is a way to fix it, using centuries old techniques that have been proven time and again in the field of industrial engineering i.e. using demand for products/services to determine the resourcing required to meet this demand. One major reason that this process probably hasn’t been adopted in Higher Education (or indeed a range of other industries) is that the calculation of the fully burdened unit cost, based on robust cause and effect allocations can be quite a large, complex and manual process. However, over the last two decades this process has been refined and systemized to enable these detailed unit costs to be calculated relatively quickly using the Pilbara Insights solution. These unit costs can then be used for institution-wide Resource Consumption Budgeting or as a starting point, creating budgets for new and existing programs using the Academic Decision Assistance Model (ADAM) tool. It’s important to resolve this issue because budgets drive change more than strategic plans, so if the institution needs to change to address all of the current challenges to Higher Ed, then it’s the budget that will drive this change.