TLDR!

- Activity-Based Costing (ABC) concepts have been around for yonks! (Australian/British slang for a long time) Ever since the 1770’s.

- ABC concepts have been largely ignored for yonks!

- ABC was formalized in the 1980’s.

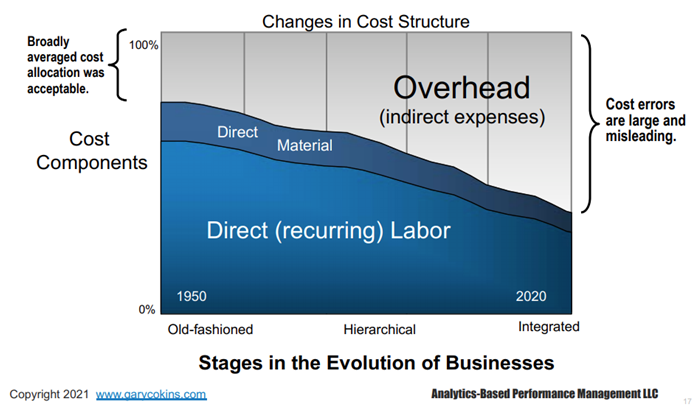

- ABC is needed more than even now given the increasing complexity of modern business models and the growth of overhead to manage these organizations.

- Oh, and Charles Darwin is Josiah Wedgwood’s grandson!

What is Activity-Based Costing?

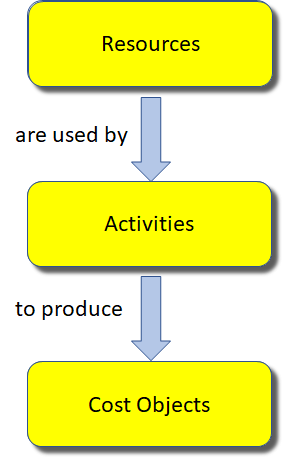

It’s a method of calculating costs by tracing resources (people, facilities, equipment, cash) through the Activities (what gets done) inside an organization through to the final Cost Objects (what is produced – products/services) using cause and effect drivers. Fundamentally, ABC is a very simple concept:

Although quite simple, ABC can have very complex implementations. ABC only takes days to learn, but decades to master!

A Brief History of Activity-Based Costing

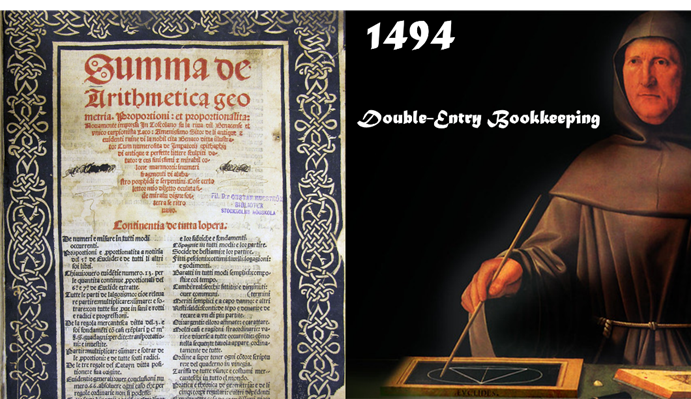

15th Century

Traditional Accounting can trace its roots back to 1494 when Luca Bartolomeo de Paciolo published his mathematics manuscript containing what is still considered the blue print for accounting – double-entry bookkeeping.

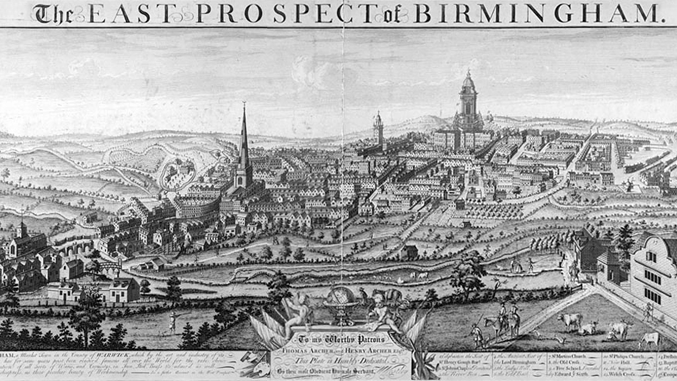

18th Century

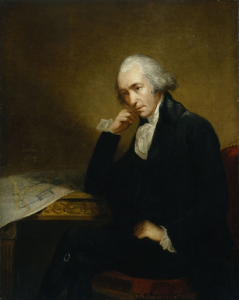

1790’s – Roll the clock forward 300 years to Industrial Era Birmingham.

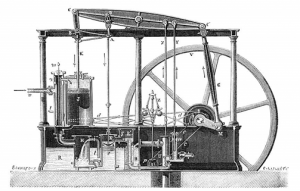

James Watt is a keen user of double-entry bookkeeping. When he and Matthew Boulton start making steam engines, they needed a way to determine a price to sell them for because there was no established market for steam engines yet. Unfortunately, traditional bookkeeping didn’t provide this information, so they created “job costing” to figure out how much it actually cost to build their engines, they could then determine a price that would provide them with a suitable profit.

James Watt is a keen user of double-entry bookkeeping. When he and Matthew Boulton start making steam engines, they needed a way to determine a price to sell them for because there was no established market for steam engines yet. Unfortunately, traditional bookkeeping didn’t provide this information, so they created “job costing” to figure out how much it actually cost to build their engines, they could then determine a price that would provide them with a suitable profit.

OK, now James knows he will make a tidy profit from selling his steam engines, but our James is a thinker! He uses his newly developed costing method to demonstrate to prospective customers how much money they can save by using his engines and proposes a lease and cost-savings sharing plan. It’s a hit and a win-win, the customers still save money overall and James has increased his profit per engine.

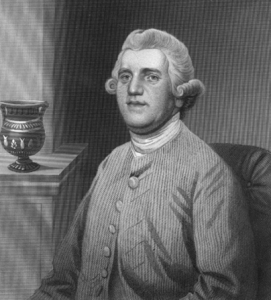

But James wasn’t the only one thinking about costs in the 1700’s. About 20 years earlier Josiah Wedgwood had a roaring business selling tea sets and dinner plates but struggled to make a profit! Why, he thought, did he have lots of sales but no profit? So, he looked at his detailed accounting records and

But James wasn’t the only one thinking about costs in the 1700’s. About 20 years earlier Josiah Wedgwood had a roaring business selling tea sets and dinner plates but struggled to make a profit! Why, he thought, did he have lots of sales but no profit? So, he looked at his detailed accounting records and teased out all of the costs. He noted that some expenses and I quote here “are much the same whether the quantity of goods made be larger or small”. So, he broke up his expenses into equipment, labour, admin and selling expenses and noted how each effected his profitability. This was noted by his biographer as “an exercise in self-taught cost accounting and one of the earliest documents of its kind in the history of manufacturing.” When a credit crisis hit Britain in 1772 and prices collapsed, Wedgwood was able to adapt by trimming the right costs! Without this his company could have easily failed.

teased out all of the costs. He noted that some expenses and I quote here “are much the same whether the quantity of goods made be larger or small”. So, he broke up his expenses into equipment, labour, admin and selling expenses and noted how each effected his profitability. This was noted by his biographer as “an exercise in self-taught cost accounting and one of the earliest documents of its kind in the history of manufacturing.” When a credit crisis hit Britain in 1772 and prices collapsed, Wedgwood was able to adapt by trimming the right costs! Without this his company could have easily failed.

And here’s an interesting fact for your next pub trivia night – Charles Darwin is Wedgwood’s grandson. Charles actually married his first cousin Emma Wedgwood, which was quite common at the time, to keep money and influence in the family. But Charles was very concerned about his children’s health based on his own studies of plant inbreeding. He was so concerned he actually lobbied in 1870 to get questions about first-cousin marriages added to the census, but he was unsuccessful.

And here’s an interesting fact for your next pub trivia night – Charles Darwin is Wedgwood’s grandson. Charles actually married his first cousin Emma Wedgwood, which was quite common at the time, to keep money and influence in the family. But Charles was very concerned about his children’s health based on his own studies of plant inbreeding. He was so concerned he actually lobbied in 1870 to get questions about first-cousin marriages added to the census, but he was unsuccessful.

19th Century

OK, back to the costing stuff – if we jump forward in time almost 100 more years, we come across Railroad engineer, and creator of an innovative truss used for railroad bridges, Albert Fink. Fink was also fascinated with costs and divided costs into four categories:

OK, back to the costing stuff – if we jump forward in time almost 100 more years, we come across Railroad engineer, and creator of an innovative truss used for railroad bridges, Albert Fink. Fink was also fascinated with costs and divided costs into four categories:

- maintenance and overhead that did not vary with the volume of traffic;

- station personnel expenses that varied only with volume of freight;

- fuel and other operating expenses which varied with the number of train miles run; and

- fixed charges for interest.

He evaluated operating expenses using cost per ton/mile and monitored costs per ton/mile for the entire railroad and determined the reasons for cost differences among subunits.

“He used his considerable professional skills to expand railroads in the United States, to develop management tools for the efficient operation of individual railroads, and to create institutions for the efficient and, most significantly, profitable management of the railway system in the United States.” https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/albert-fink/

20th Century

1910 – The development of cost accounting comes to an abrupt halt – usage of cost accounting expands, but concepts and methods are frozen for the next three-quarters of a century. This may have been the result of the collection of cost information becoming very difficult and expensive for a widening range of products making it harder to justify its benefits. In its place, there appeared various costing procedures that 20th Century accountants adopted to evaluate cost of inventories for financial reports. However, while this kind of cost information was reliable for evaluating cost of inventories and financial reporting, it was irrelevant and even misleading for decision making needs, particularly for strategic product decisions. Other possible causes were the lack of advancement in decision science – there was little or no demand for better cost or management accounting information – and the Western world’s lack of competition for the major goods and services they provided.

1923 – John Maurice Clark publishes “Studies in the Economics of Overhead Costs” In his book, Clark discussed fixed and variable costs; joint, sunk, differential and residual costs; short and long run fluctuations; and a number of other issues from the economist’s point of view. He also advocated that different costs should be used for different purposes, i.e., the cost information used for decision making should be different from that of financial requirements. This book is considered by most researchers and historians as one of the major contributions to cost accounting literature, but it was pretty much ignored for the next 60 years.

long run fluctuations; and a number of other issues from the economist’s point of view. He also advocated that different costs should be used for different purposes, i.e., the cost information used for decision making should be different from that of financial requirements. This book is considered by most researchers and historians as one of the major contributions to cost accounting literature, but it was pretty much ignored for the next 60 years.

Three key takeaways from his book are:

- There are different costs for different purposes.

- A management accountant has to think; not just memorize mechanics.

- Management accounting consists of concepts to be applied, not forms to be filled in…this isn’t “painting by the numbers”

1929 – The Great Crash!

1933 – President Roosevelt introduces the ‘Truth in Securities’ legislation, which meant companies that issued stocks and bonds would have to publish independently audited accounts, giving the accountancy profession a statutory role! I suspect that this may be a turning point for the accounting profession, putting more importance on financial and tax accounting and less on management accounting.

1933 – President Roosevelt introduces the ‘Truth in Securities’ legislation, which meant companies that issued stocks and bonds would have to publish independently audited accounts, giving the accountancy profession a statutory role! I suspect that this may be a turning point for the accounting profession, putting more importance on financial and tax accounting and less on management accounting.

1980 – The introduction of personal computing and the increasing computation power of advanced technology eliminates many of the obstacles that thwarted the development of management accounting earlier in the century. Accountants only use the new technology to implement the obsolete concepts from 1910 more efficiently.

1987 – Robert Kaplan and Robin Cooper re-introduce an updated version of the cause-and-effect driven product costing methodology given birth by Fink in 1860 and christen it Activity-Based Costing.

1990 the Consortium for Advanced Manufacturing (later changed to Management) – International (CAM-I) adds a Process View to the Cost Assignment View and develops the CAM-I Cross.

1990 – 2022 After renewed interest in ABC, there was a huge increase in the number of ABC models developed around the world, however by early 2000’s it quickly dropped off. This was driven by the fact that a lot of these models were too complex and required a lot of manual maintenance and updating.

The complexity of the models made it difficult for key stakeholders to understand the model. If they couldn’t understand the model, the didn’t trust the model. If they didn’t trust the model, they didn’t use the model.

The large amount of manual effort required to keep models up-to-date meant that, in short, it cost too much to calculate cost!

Because it required a lot of manual effort and key stakeholders weren’t using it, ABC quickly died off. However, there were an intrepid bunch of folk around the planet who believed in the benefits of ABC and knew all too well the pitfalls, so spent many years perfecting their solutions.

The implementation of ABC today is a bit different to the 1990s. Firstly, the initial models implemented are simpler and then complexity can be layered in over time by addressing the specific business requirements of key stakeholders. Secondly the models are more automated now, this includes both the initial build and the update processes, which makes it a much more efficient system.

Why use Activity-Based Costing?

So why do we need to implement ABC? ABC provides tremendous insight into the inner workings of your organization. However, the more pressing reason now, is that businesses are becoming much more complex (lots of different products/services to lots of different customers through lots of different channels) and the amount of overhead to support these complex businesses, in a more regulated world, is increasing as well.

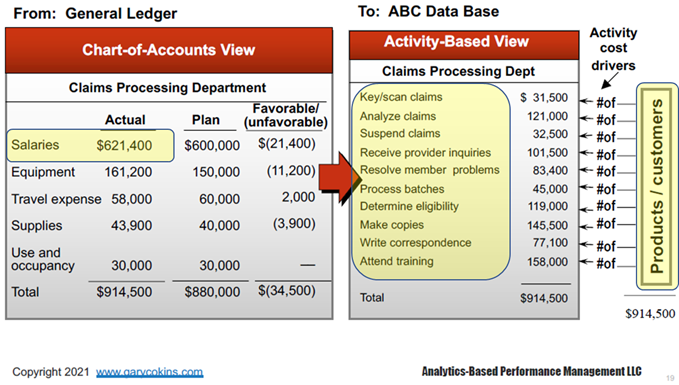

Just like back in Watt’s, Wedgwood’s and Fink’s day, the traditional accounting systems of today do not provide the full cost data required to manage these organizations. Luckily it’s all electronic now, rather than big books with data written in freehand, but the fundamental problem is the same. Cost is a function of Resources consumed. The accounting system shows you what has been spent but not what things cost. For example – you can see how much is spent on salaries, but not what those people do and which products/ services or customers they contribute to.

But an even bigger problem, that ABC is used to resolve, is what to do with this ever increasing OVERHEAD!

In Wedgwood’s example the direct costs of equipment, production labour and direct selling expenses are reasonably easy to determine. The section he labels as Admin, which is overhead, can get quite complicated. In his day admin and overhead were probably only a small component of the total cost, but today, driven by complexities and regulations mentioned earlier, overhead has been increasing so that it is now a major component of total cost.

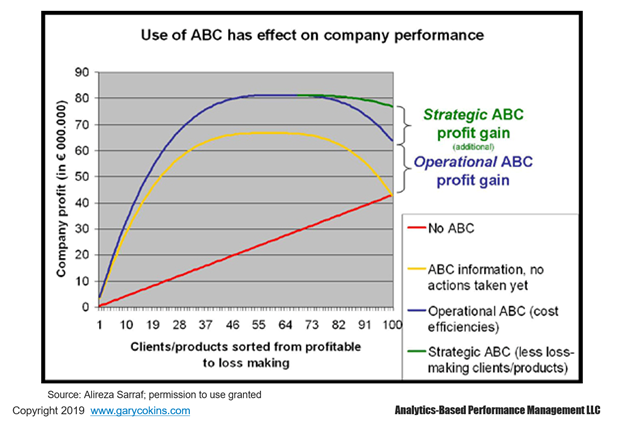

So it is essential that overhead is allocated appropriately or you could incorrectly calculate the full cost of a product thus impacting pricing decisions and profitability.

And therein is one of the other major benefits of ABC – the ability to get a detailed picture of individual product and service profitability. This allows you to actively manage and increase individual and overall profitability for the organization. This is a very powerful tool to have at your disposal. This is true for Not-For-Profit organizations as well, even though they are driven more by mission rather than profit. To enable Not-For-Profits to achieve their mission in a sustainable fashion, they must ensure they make more money than they spend. As a wise former university financial manager once said, “we might be Not-For-Profit but we are also Not-For-Loss! “

But companies calculate their costs now, without ABC, how do they do that?

Mostly with ad-hoc spreadsheets.

This has a number of problems though:

- Spreadsheets are prone to errors,

- Spreadsheets can only handle a certain amount of data before falling over, and

- Ad-hoc analysis creates islands of analysis throughout the organization, leading to arguments about whose numbers are the correct numbers.

These ad-hoc spreadsheets are more than likely using ABC principles anyway, if an analyst has to calculate the full cost and profitability of a product/service then they will need to find all the appropriate resources (people, equipment, facilities, cash), the costs associated with those resources and allocate them in some fashion to the product or service they are analyzing. This approach is very inefficient!

What’s needed is a centralized, standardized and systemized way of calculating cost for the entire organization!

A properly developed Activity-Based Costing solution can meet this need!

References:

There were several reference materials I used for this blog post. One source was a book written by Richard Brooks “Bean Counters: The Triumph of the Accountants and how they Broke Capitalism”. I highly recommend this book to dig into the history of accounting and the various shenanigans that occurred throughout history. I should state though that I’m not anti-accounting, just interested in how we got to where we are now.

There were several reference materials I used for this blog post. One source was a book written by Richard Brooks “Bean Counters: The Triumph of the Accountants and how they Broke Capitalism”. I highly recommend this book to dig into the history of accounting and the various shenanigans that occurred throughout history. I should state though that I’m not anti-accounting, just interested in how we got to where we are now.

Many thanks also to Gary Cokins and Doug Hicks for sharing their own articles, papers and presentations.

You can find Gary’s work here: https://www.garycokins.com/

You can find Gary’s work here: https://www.garycokins.com/

And Doug’s work here: http://www.dthicksco.com/

And Doug’s work here: http://www.dthicksco.com/

If you would like more information on this topic I would recommend these two groups:

https://www.profitability-analytics.org/

Can these models help answer the question of whether a university should implement

differential tuition for each academic program?

Asking for a friend.

Hi Robert, thanks for your question and please tell your friend that, yes, we can test differential tuition for each academic program. We can do this in three different ways.

The first way by using the Rapid/Executive/Strategic Insights model to build different scenarios based on different tuition for various programs and compare the margin differential, this assumes student numbers remain the same.

The second way is to use the Predictive Insights model, this allows you to build different scenarios for differing tuition but also to change student numbers as well, if you believe the change in tuition will increase or decrease student numbers in different programs. The predictive model will then calculate the required teaching load for this increase or decrease in students and also the support and overhead costs, to provide a fully-burdened cost of teaching the Programs. The model will then calculate the new margins based on the various tuition rates set, and these can be easily compared.

The third way is by using a hybrid of both of these with our quasi-predictive model, the ADAM Tool. This tool is attached to the Executive/Strategic model and is used to test the five year financial performance of Programs. This tool allows you to enter changes in tuition plus changes in student numbers but only for one program at a time. So you would need to repeat this process for multiple Programs.

Hope this helps.